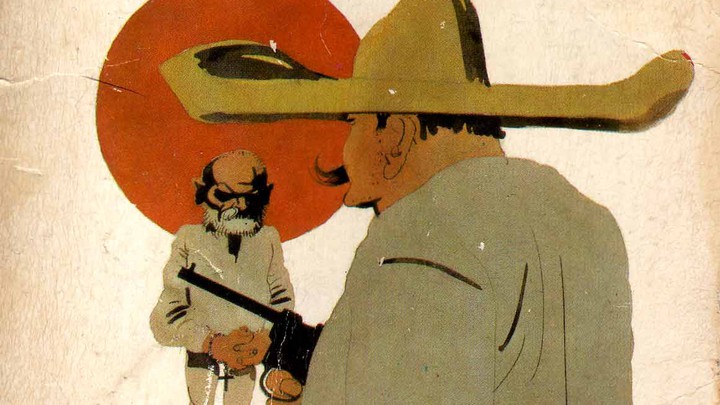

Translation into Spanish of an extract from the first chapter of The Power and The Glory written by British author Graham Greene. The novel was published in 1940 and is one of Greene’s most celebrated works of literature.

The story takes place in Mexico during the religious persecution of the 1930s and the hero is a nameless priest referred to as the “whiskey priest” who is on the run from the Mexican authorities. “A violent, raw novel about suffering, strained faith, and ultimate redemption.”

The Power and The Glory

The stranger had left his book behind. It lay under his rocking-chair: a woman in Edwardian dress crouched sobbing upon a rug embracing a man’s brown polished pointed shoes. He stood above her disdainfully with a little waxed moustache. The book was called La Eterna Martyr. After a time Mr. Tench picked it up. When he opened it he was taken aback-what was printed inside didn’t seem to belong; it was Latin. Mr. [14] Tench grew thoughtful: he picked the book up and carried it into his workroom. You couldn’t burn a book, but it might be as well to hide it if you were not sure–sure, that is, of what it was all about. He put it inside the little oven for gold alloy. Then he stood by the carpenter’s bench, his mouth hanging open: he had remembered what had taken him to the quay-the ether cylinder which should have come down-river in the General Obregon. Again the whistle blew from the river, and Mr. Tench ran without his hat into the sun. He had said the boat would not go before morning, but you could never trust those people not to keep to time-table, and sure enough, when he came out onto the bank between the customs and the warehouse, the General Obregon was already ten feet off in the sluggish river, making for the sea. He bellowed after it, but it wasn’t any good: there was no sign of a cylinder anywhere on the quay. He shouted once again, and then didn’t trouble any more. It didn’t matter so much after all: a little additional pain was hardly noticeable in the huge abandonment.

On the General Obregon a faint breeze began to blow: banana plantations on either side, a few wireless aerials on a point, the port slipped behind. When you looked back you could not have told that it had ever existed at all. The wide Atlantic opened up: the great grey cylindrical waves lifted the bows, and the hobbled turkeys shifted on the deck. The captain stood in the tiny deck-house with a toothpick in his hair. The land went backward at a slow even roll, and the dark came quite suddenly, with a sky of low and brilliant stars. One oil-lamp was lit in the bows, and the girl whom Mr. Tench had spotted from the bank began to sing gently-a melancholy, sentimental, and contented song about a rose which had been stained with true love’s blood. There was an enormous sense of freedom and air upon the gulf, with the low tropical shore-line buried in darkness as deeply as any mummy in a tomb. I am happy, the young girl said to herself without considering why, I am happy. (Graham Greene)

El poder y la gloria

El extraño se había olvidado su libro —había quedado debajo de la mecedora—, en cuya portada aparecía una mujer que tenía puesto un vestido de la época eduardiana y estaba en cuclillas sobre una alfombra: sollozaba abrazada a los zapatos marrones, lustrados y puntiagudos de un caballero. El hombre, quien estaba parado y lucía un pequeño bigote encerado, la miraba desde arriba con desprecio. El libro se llamaba La eterna mártir. Después de un rato, el señor Tench lo alzó. Cuando lo abrió, se sorprendió: el contenido no parecía corresponder a ese título; estaba en latín. El señor Tench se quedó pensando… luego volvió a tomarlo y lo llevó a su sala de trabajo. Le resultaría imposible quemar un libro, pero, al no estar del todo seguro sobre qué trataba, lo mejor era esconderlo. Así es que decidió colocarlo dentro del hornillo para fundir oro. Luego, de pie junto al banco de madera, boquiabierto, recordó por qué había ido al muelle: por el tubo de éter que vendría en el General Obregón. Volvió a oír el silbato de aviso en el río y salió corriendo bajo el sol sin su sombrero. Acababa de decir que el barco no saldría hasta la mañana siguiente, pero claro, uno no puede confiar siempre en que esas personas no vayan a respetar el horario. Así es que, por supuesto, cuando llegó a la ribera, entre la aduana y el depósito, el General Obregón ya se había adentrado unos tres metros en ese río de aguas perezosas y se dirigía hacia el mar. Gritó con todas sus fuerzas, pero no sirvió de nada; en el muelle, no había rastro alguno de un tubo en ninguna parte. Gritó una vez más, pero luego desistió. Después de todo, no era tan importante: un poco más dolor en tan desoladora realidad era casi imperceptible.

A bordo del General Obregón, comenzó a soplar una suave brisa. Se veían plantaciones de bananas a ambos lados y se divisaban algunas antenas a lo lejos. En la distancia, el puerto iba ya esfumándose; al volver la mirada, parecía como si nunca hubiera existido. La inmensidad del Atlántico hizo su apertura triunfal: las enormes y cilíndricas olas grises alzaban la proa y arrastraban de un lado a otro a los pavos maniatados que estaban en la cubierta. El capitán, quien llevaba un mondadientes en el cabello, se encontraba de pie en la caseta de la cubierta. El pedazo de tierra fue quedando atrás a ritmo lento y homogéneo y, bastante de repente, cayó la noche, con un cielo de estrellas bajas y brillantes. Una lámpara de gas se encendió en la proa y la joven, a quien el señor Tench había alcanzado a ver desde la ribera, comenzó a entonar, con voz suave, una canción melancólica, sentimental, a la vez que alegre, acerca de una rosa que se había manchado con la sangre del verdadero amor. Se percibía una gran sensación de libertad y respiro en el golfo. Y el bajo horizonte tropical ya había quedado enterrado en la oscuridad más profunda, cual momia en una tumba. “Me siento feliz”, se dijo la joven a sí misma sin saber por qué, “me siento feliz”.