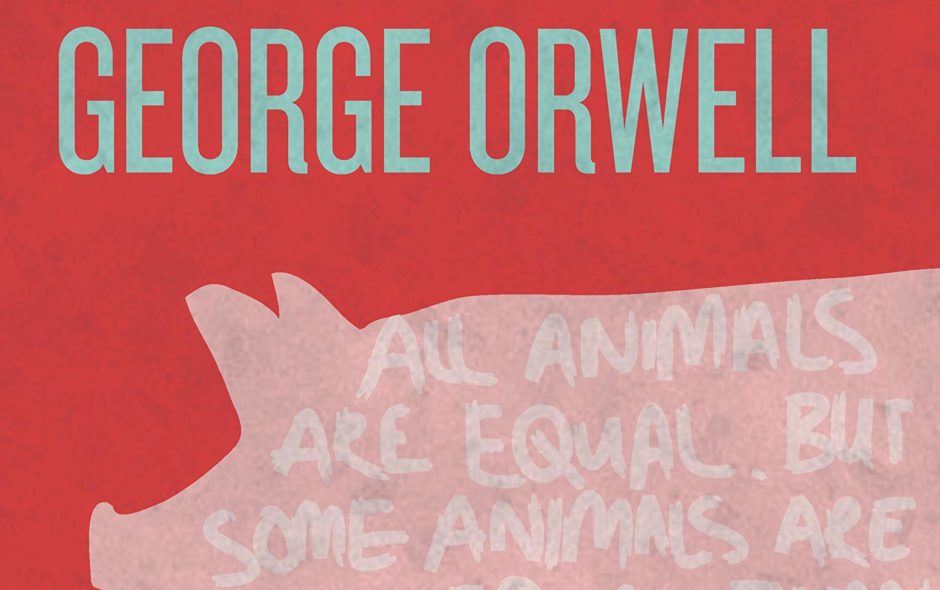

Translation into Spanish of the first part of Animal Farm, a novel written by George Orwell and first published in England on the 17th of August, 1945. The book tells the story of “a revolution that went wrong.”

Animal Farm

Mr. Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes. With the ring of light from his lantern dancing from side to side, he lurched across the yard, kicked off his boots at the back door, drew himself a last glass of beer from the barrel in the scullery, and made his way up to bed, where Mrs. Jones was already snoring.

As soon as the light in the bedroom went out there was a stirring and a fluttering all through the farm buildings. Word had gone round during the day that old Major, the prize Middle White boar, had had a strange dream on the previous night and wished to communicate it to the other animals. It had been agreed that they should all meet in the big barn as soon as Mr. Jones was safely out of the way. Old Major (so he was always called, though the name under which he had been exhibited was Willingdon Beauty) was so highly regarded on the farm that everyone was quite ready to lose an hour’s sleep in order to hear what he had to say.

At one end of the big barn, on a sort of raised platform, Major was already ensconced on his bed of straw, under a lantern which hung from a beam. He was twelve years old and had lately grown rather stout, but he was still a majestic looking pig, with a wise and benevolent appearance in spite of the fact that his tushes had never been cut. Before long the other animals began to arrive and make themselves comfortable after their different fashions. First came the three dogs, Bluebell, Jessie, and Pincher, and then the pigs, who settled down in the straw immediately in front of the platform. The hens perched themselves on the window-sills, the pigeons fluttered up to the rafters, the sheep and cows lay down behind the pigs and began to chew the cud. The two cart-horses, Boxer and Clover, came in together, walking very slowly and setting down their vast hairy hoofs with great care lest there should be some small animal concealed in the straw. Clover was a stout motherly mare approaching middle life, who had never quite got her figure back after her fourth foal. Boxer was an enormous beast, nearly eighteen hands high, and as strong as any two ordinary horses put together. A white stripe down his nose gave him a somewhat stupid appearance, and in fact he was not of first-rate intelligence, but he was universally respected for his steadiness of character and tremendous powers of work. After the horses came Muriel, the white goat, and Benjamin, the donkey. Benjamin was the oldest animal on the farm, and the worst tempered. He seldom talked, and when he did, it was usually to make some cynical remark-for instance, he would say that God had given him a tail to keep the flies off, but that he would sooner have had no tail and no flies. (…)

Rebelión en la granja

El señor Jones, dueño de la granja Manor, había dado por finalizada la jornada. Cerró con llave los gallineros, pero estaba muy ebrio como para acordarse de también cerrar las trampillas. Con el halo de luz de su linterna que se bamboleaba de un lado a otro, cruzó el patio tambaleándose, se quitó las botas en la puerta trasera, se sirvió un último vaso de cerveza del barril que estaba en la cocina y caminó como pudo hasta su cama, donde se encontraba la señora Jones, que ya estaba roncando.

En cuanto se apagó la luz del dormitorio, empezó el ajetreo en todas las dependencias de la granja. Durante el día, se había corrido la voz de que el cerdo Viejo Mayor, ganador del premio en la raza middle white, había tenido un sueño extraño la noche anterior y deseaba compartirlo con el resto de los animales. Habían acordado que todos concurrirían al establo grande apenas estuvieran seguros de que el señor Jones ya no andaba cerca. El Viejo Mayor (así es como siempre lo llamaban a pesar de que su nombre de exhibición había sido la Belleza de Willingdon) tenía tanto prestigio dentro la granja que todos estaban dispuestos a perder una hora de sueño con tal de poder escuchar lo que quería contarles.

En uno de los extremos del enorme establo, sobre una especie de plataforma elevada, Mayor ya se encontraba cómodamente arrellanado sobre su colchón de paja, debajo de un farol que colgaba de una de las vigas. Tenía doce años y, aunque últimamente se había puesto bastante corpulento, seguía siendo un cerdo de porte majestuoso y de aspecto sabio y benevolente, a pesar de que nunca le habían cortado la cola. Muy pronto, los demás animales comenzaron a llegar y a acomodarse según les resultara más conveniente en función de sus estructuras corporales. Primero llegaron los tres perros, Bluebell, Jessie y Pincher, y luego los cerdos, quienes se ubicaron sobre la paja justo en frente de la plataforma. Las gallinas se posaron sobre las repisas de las ventanas, las palomas revoloteaban entre las vigas del techo, las ovejas y las vacas se sentaron detrás de los cerdos y comenzaron a rumiar. Los dos caballos de tiro, Boxer y Clover, entraron juntos caminando a paso bien lento y asentando las peludísimas pezuñas con mucho cuidado por las dudas hubiera algún animal pequeño escondido entre la paja. Clover era una yegua corpulenta de aspecto maternal que no había podido recuperar su figura después de dar a luz a su último potrillo y que ya casi estaba llegando a la mitad de su vida. Boxer era una bestia enorme, de casi dos metros de altura y con la fuerza de dos caballos normales juntos. Tenía una raya blanca debajo de la nariz que le otorgaba una apariencia algo estúpida y, de hecho, no era ninguna lumbrera, pero todos lo respetaban por su carácter firme y su impresionante capacidad de trabajo. Después de los caballos, apareció Muriel, la cabra blanca, y Benjamín, el burro. Benjamín era el animal más viejo de la granja y el más malhumorado. Casi nunca hablaba y, cuando lo hacía, en general era para hacer algún comentario cínico, por ejemplo, solía decir que Dios le había dado una cola para espantar a las moscas, pero que él hubiera preferido no tener cola y que las moscas no existieran. (…)